The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the government of Suriname and multinational company Chinalco is controversial and conflicts with agreements regarding land rights with indigenous communities and tribal peoples in the region where activities are planned. The government has disregarded the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC).

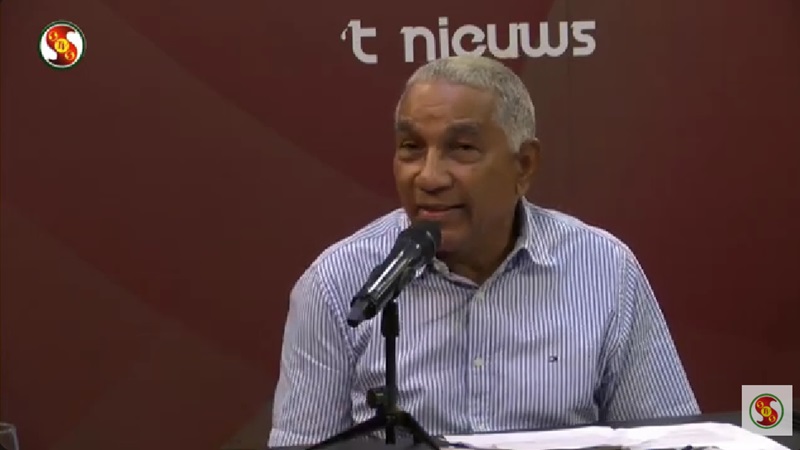

This principle requires that permission is obtained from local communities in the interior before initiating economic activities in their territories, ensuring their lands are not harmed. According to Professor Jack Menke, initial efforts to follow the FPIC procedure were abandoned, leading to the signing of the MoU without the involvement of residents from Apoera, Washabo, and Section. The affected communities have since expressed their dissatisfaction with this process.

In an interview with STVS, Menke highlighted several overlooked aspects, noting that the Bakhuys region—where the activities are planned—is at the heart of pristine Suriname, boasting unique flora and fauna. He questioned the absence of environmental studies assessing the impact of these activities.

Menke also criticized the use of the term Local Content, often included in agreements like this MoU. He argued that Local Content addresses only a small part of the issue, while the focus should be on Local Development, which involves creating tangible benefits for communities through proper consultation and projects that directly contribute to their progress.

Drawing on his research into the bauxite sector, Menke pointed out that the anticipated economic benefits from Suralco’s operations between 1816 and 1916 did not materialize. An exception occurred after 1964, when economic growth of 8–10% was recorded for three years. Despite bauxite contributing over 75% of export revenues, there was no fair distribution of wealth.

Menke recalled the West Suriname Project, which involved ambitious plans for bauxite mining but faced intense protests from local communities due to its poor execution. Land rights were inadequately addressed at the time—a problem that persists today.

Through his work, Menke frequently visits indigenous areas and observes a deep sense of unease among residents. He emphasized that without dialogue and respect for their rights, projects like this will only lead to greater division and harm.